Pencetakan buku adalah upaya kolaboratif, seperti yang kita lihat di sini dengan orang-orang yang berbeda mempersiapkan sebuah buku untuk mesin cetak. Jan Collaert I setelah Joannes Stradanus, “Penemuan Pencetakan Buku, " di dalam Penemuan Baru Zaman Modern (Nova Reperta), piring 4, C. 1600, ukiran di atas kertas, 27 x 20 cm (Museum Seni Metropolitan)

Mesin cetak bisa dibilang salah satu penemuan paling revolusioner dalam sejarah dunia modern awal. Sementara tukang emas dan penerbit Jerman abad ke-15, Johannes Gutenberg, digembar-gemborkan untuk ciptaannya dari mesin cetak mekanis yang memungkinkan produksi massal gambar dan teks, teknologi tipe bergerak pertama kali dirintis jauh lebih awal di Asia Timur. Di Cina awal abad kesebelas, pengrajin Bi Sheng menemukan bahwa ia dapat membuat karakter Cina individu dari tanah liat yang dipanggang untuk menciptakan sistem tipe bergerak. Nanti, di Korea abad ketiga belas, jenis logam bergerak pertama yang diketahui diproduksi.

Halaman dari buku tertua di dunia yang dicetak dengan jenis logam yang dapat dipindahkan, Antologi Ajaran Zen Pendeta Buddhis Agung , 1377, 24. 5 x 17 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Peningkatan kontak dan pertukaran antar budaya di Asia Timur dan Eropa melalui Jalur Sutra, dimulai pada abad ketiga belas, menyebabkan penyebaran inovasi pencetakan tersebut. Memang, pada pertengahan 1400-an, Gutenberg berada dalam posisi utama untuk merancang proses mekanisnya untuk mencetak banyak sumber tekstual dan representasi visual yang sama, yang, berkat dukungan kertas portabel dan lebih terjangkau, berarti mereka bisa diedarkan secara luas, berfungsi sebagai mode awal komunikasi massa di era pra-digital. Penerbitan cetakan ditambah dengan pengenalan jenis bergerak menawarkan kemungkinan yang belum pernah terjadi sebelumnya untuk pertukaran pengetahuan dan ide lintas budaya, serta gaya dan desain artistik.

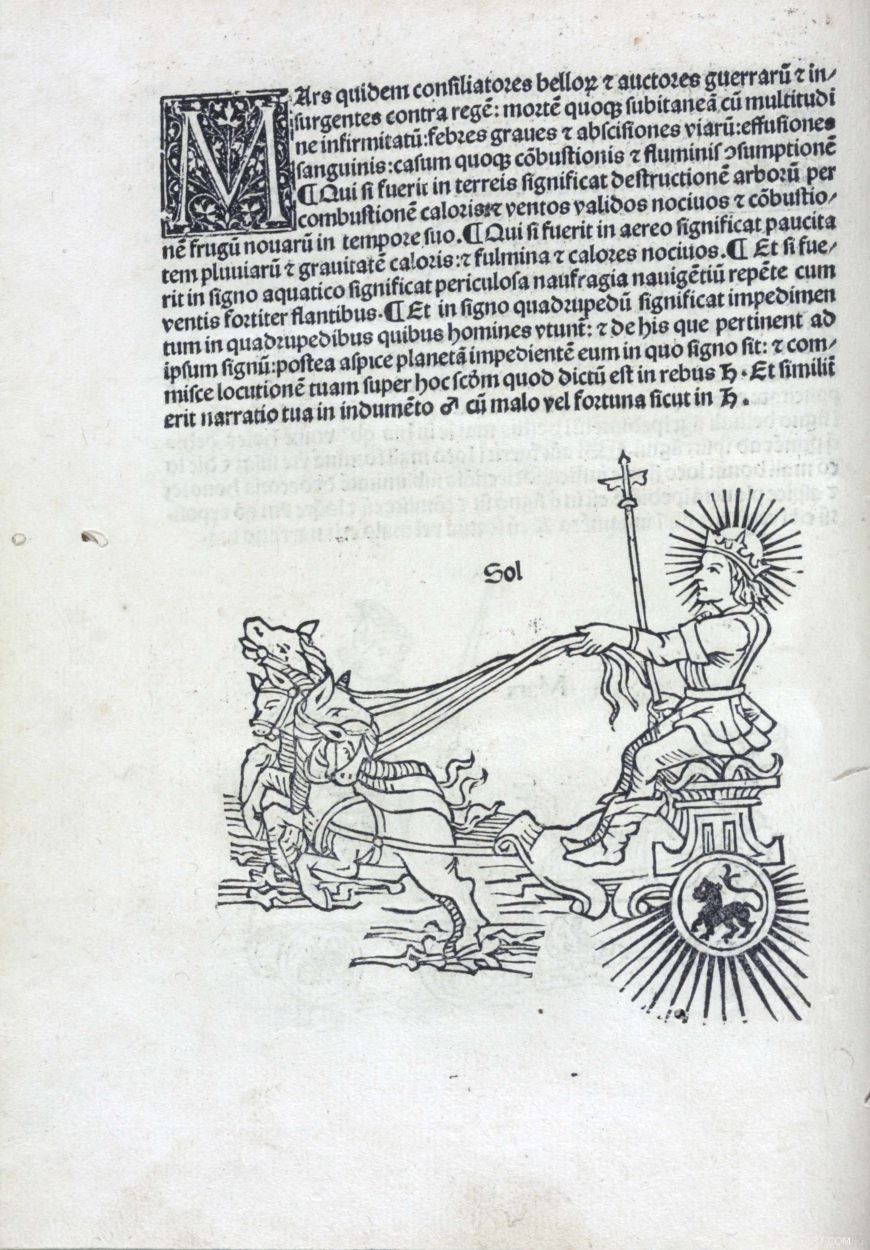

Ilustrasi ini berasal dari buku yang diterbitkan oleh Erhard Ratdolt, printer Jerman awal dari Augsburg, dan diilustrasikan dengan tujuh puluh tiga potongan kayu. Di sini kita melihat “Sol” atau “Sun, ” di Albumasar, Astrologi Flores (Augsburg:Erhard Ratdolt, 18 November, 1488), gambar 22 (Koleksi Rosenwald, Divisi Buku Langka dan Koleksi Khusus, Perpustakaan Kongres)

Demokratisasi seni

Sebelum abad kelima belas, karya seni seperti altarpieces, potret, dan barang-barang mewah lainnya terutama ditemukan di kediaman para pelindung kaya dan di gereja-gereja karena elit sosial dan pemimpin agama di masyarakatlah yang memiliki sumber keuangan untuk memesan benda-benda indah ini. Format cetak yang dapat direproduksi dan ketersediaan kertas yang semakin meningkat memberikan kelas menengah yang berkembang, yang mungkin tidak memiliki sarana untuk membeli lukisan atau patung, kesempatan untuk mengumpulkan representasi artistik. Sementara proyek skala besar masih didanai oleh patron kaya, sebagian besar cetakan dibeli karena spekulasi. Hasil dari, kita melihat berbagai materi pelajaran yang digambarkan dalam cetakan yang akan menarik bagi kolektor yang beragam. Contohnya, keinginan untuk mempelajari masa lalu, literatur, dan sains di kota-kota di seluruh Eropa modern awal mendorong para pembuat seni grafis untuk memasok pasar seni dengan representasi sejarah kuno, mitologi klasik, dan alam dunia.

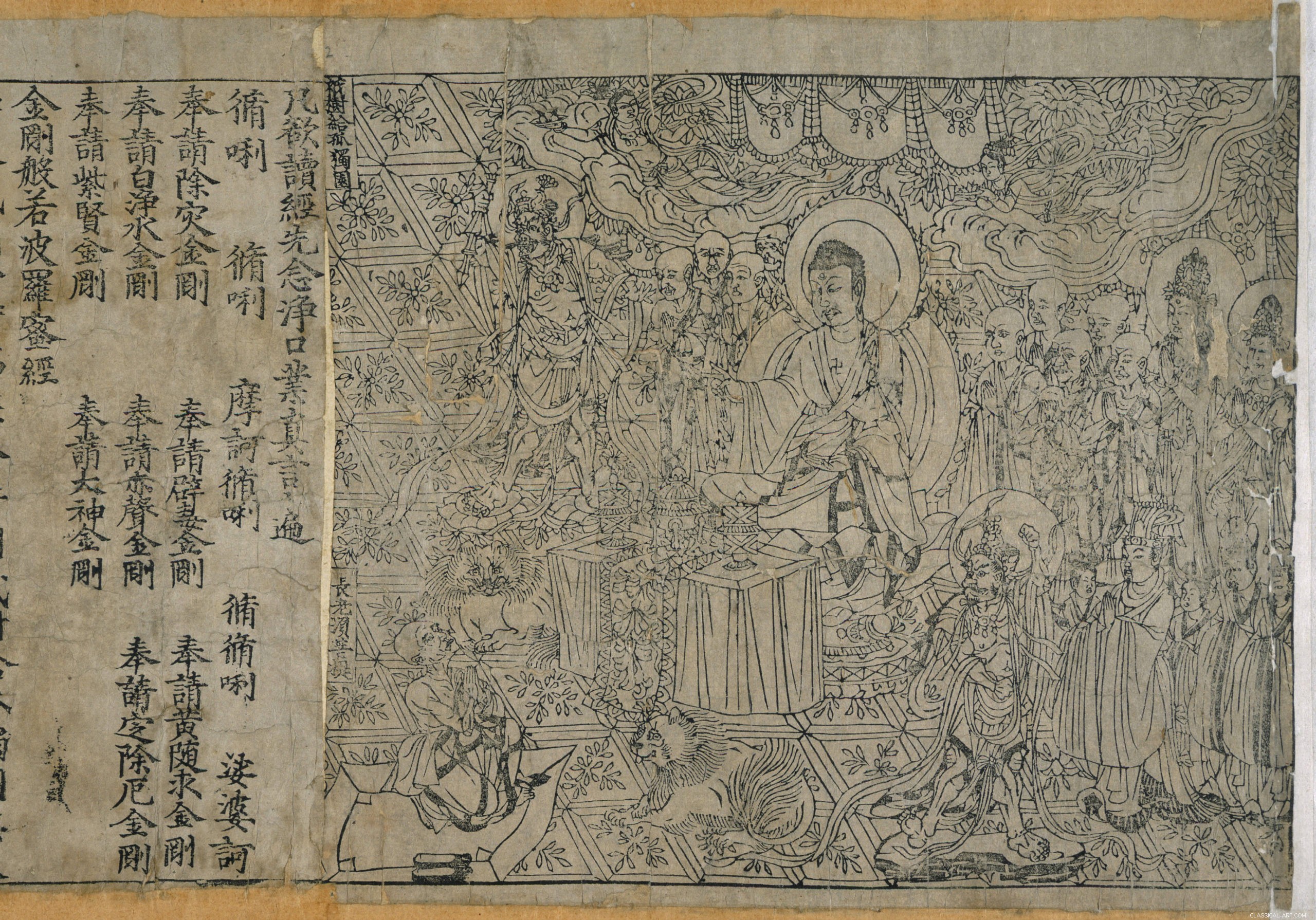

Sutra Berlian , 868, gulungan yang dicetak dengan balok kayu, ditemukan di Gua Mogao (atau "Tanpa taranya") atau "Gua Seribu Buddha, ” yang merupakan pusat Buddhis utama dari abad ke-4 hingga ke-14 di sepanjang Jalur Sutra (Perpustakaan Inggris)

Ukiran kayu

Bentuk seni grafis tertua adalah potongan kayu. Pada awal Dinasti Tang (dimulai pada abad ketujuh) di Cina, balok kayu digunakan untuk mencetak teks ke potongan tekstil, dan kertas kemudian. Pada abad kedelapan, pencetakan balok kayu telah berlangsung di Korea dan Jepang. Meskipun praktik mencetak sumber tertulis adalah bagian dari tradisi yang jauh lebih tua di Asia Timur, produksi citra cetak menggunakan balok kayu adalah fenomena yang lebih umum di Eropa, dimulai pada akhir abad keempat belas Jerman dan kemudian menyebar ke Belanda dan selatan Pegunungan Alpen Swiss ke wilayah Italia utara.

Potongan kayu awal sering menunjukkan materi pelajaran agama. Di sini kita melihat Perawan Maria menggendong putranya yang sudah meninggal, Yesus. Jerman Selatan, Swabia, Piet , C. 1460, ukiran kayu, tangan diwarnai dengan cat air, 38,7 x 28,8 cm (Museum Seni Cleveland, Cleveland)

Petrus Kristus, Potret seorang donor wanita berlutut di depan sebuah buku dengan cetakan tergantung di dinding di belakangnya (detail), C. 1455, minyak pada panel, 41,8 x 21,6 cm (Galeri Seni Nasional)

Selama paruh kedua abad kelima belas setelah Gutenberg menemukan mesin cetaknya, woodcuts menjadi metode yang paling efektif untuk mengilustrasikan teks yang dibuat dengan tipe movable. Hasil dari, kota-kota di Eropa—yaitu Mainz, Jerman dan Venesia, Italia—tempat seni grafis awalnya berkembang menjadi pusat penting untuk produksi buku. Metode Eropa untuk membuat gambar cetak di atas kertas menggunakan mesin press telah menyebar ke Asia Timur pada abad keenam belas, tetapi tidak diadopsi secara luas untuk tujuan artistik sampai beberapa abad kemudian selama periode Edo di Jepang ketika potongan kayu berwarna (cetakan ukiyo-e) diproduksi dalam jumlah besar.

Potongan kayu lembaran longgar Eropa paling awal menggambarkan subjek yang didominasi Kristen, berfungsi sebagai gambar kebaktian yang relatif murah. Sementara museum saat ini menyimpan cetakan dalam kotak yang dikontrol iklim untuk memastikan bahwa mereka bertahan untuk dinikmati generasi mendatang, pada abad kelima belas dan keenam belas, mereka dilipat dan dibawa oleh para peziarah dalam perjalanan mereka, dipotong dan ditempelkan ke sampul bagian dalam buku, atau ditempel di dinding rumah. Akibatnya, beberapa potongan kayu awal bertahan karena mereka sering dihancurkan melalui penggunaan terus-menerus. Belum, potongan kayu utama yang masih ada mengungkapkan karakter gaya dari jenis cetakan awal ini.

Potongan kayu ini selamat dari kebakaran. Ini menunjukkan Maria menggendong bayi Yesus, dikelilingi oleh orang-orang kudus dan pemandangan dari kehidupan Maria. Pembuat grafis abad ke-15 yang tidak dikenal, Madona Api , sebelum 1428, ukiran kayu, tangan diwarnai dengan cat, dimensi tidak diketahui (Katedral Santa Croce, Untuk, Italia)

Sebagai contoh, dua potongan kayu ( Piet dibuat di Jerman selatan dan Italia awal abad ke-15 Madona Api yang diduga selamat dari kebakaran yang menghancurkan bangunan tempat ia berada) baik menampilkan figur dan elemen pemandangan lainnya yang ditampilkan dengan garis tebal. Gambar-gambar ini menampilkan bayangan dan pola minimal, menyerupai desain stensil yang sering digunakan kolektor cat dengan tangan untuk meningkatkan daya tarik emosional komposisi. Hal ini terlihat dengan penggabungan garis-garis merah cat yang mewakili darah yang menetes dari luka Kristus di Piet mencetak.

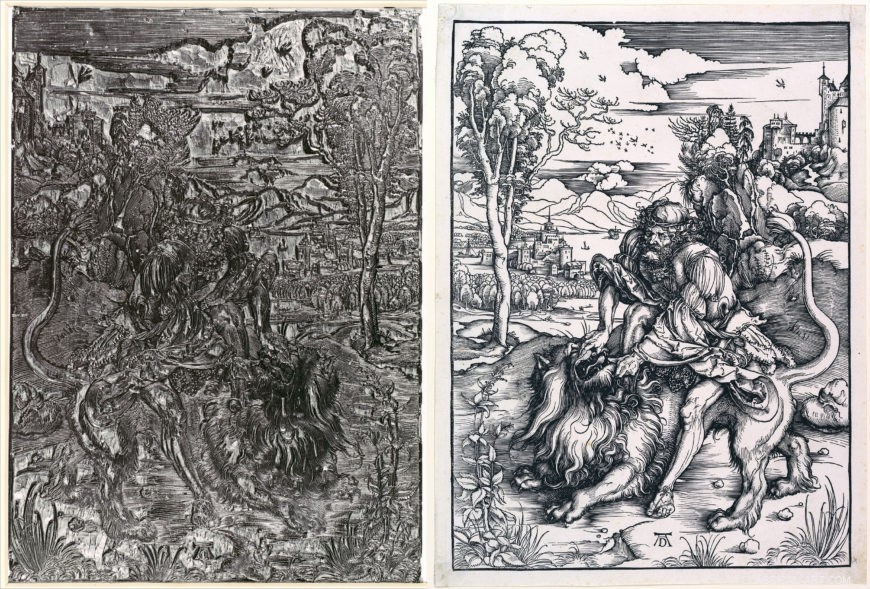

Kiri:Albrecht Dürer, balok kayu untuk Simson dan Singa , C. 1497−1498, kayu pir, 39,1 x 27,9 x 2,5 cm (Museum Seni Metropolitan); kanan:Albrecht Durer, Simson dan Singa , C. 1497−1498, ukiran kayu, 40,6 x 30,2 cm (Museum Seni Metropolitan)

Seorang seniman kontemporer menggunakan gouger genggam untuk memotong desain potongan kayu menjadi kayu lapis Jepang. Desainnya telah dibuat sketsa dengan kapur pada permukaan kayu lapis yang dicat (foto:Zephyris, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Suatu jenis proses pertolongan, potongan kayu dihasilkan dengan memberi tinta pada permukaan matriks yang ditinggikan, yang akan menghasilkan kesan cermin dari komposisi ketika blok ditekan ke selembar kertas menggunakan tekanan manual atau mekanis (mesin cetak). Stempel karet adalah contoh modern dari pencetakan relief. Untuk membuat desain pada balok kayu, seorang seniman menggunakan pisau atau gouge untuk memotong bagian kayu di antara garis dan bentuk yang akan dicetak. Saat memotong area kayu, kita harus berhati-hati untuk tidak membuat garis yang ditinggikan terlalu tipis atau garis yang ditinggikan dapat pecah ketika tekanan ditambahkan untuk menghasilkan kesan, itulah sebabnya potongan kayu awal menampilkan desain dengan kontur yang berani.

Proses relief adalah salah satu jenis utama seni grafis. Untuk membuat potongan kayu, seorang seniman menorehkan permukaan matriks yang terangkat, yang menciptakan kesan cermin komposisi ketika balok ditekan ke selembar kertas menggunakan tekanan manual atau mekanis (mesin cetak) (video dari The Museum of Modern Art).

Pada akhir abad kelima belas, seniman Jerman Albrecht Dürer menemukan cara untuk menggambarkan kehalusan tekstur dan nada yang mengesankan dalam cetakannya. Dengan mengukir serangkaian garis tipis yang saling berdekatan di Simson dan Singa , dia dengan meyakinkan mewakili bayangan di lereng bukit.

Area putih dalam cetakan ini tidak diberi tinta, berperan sebagai highlight dalam adegan tersebut. Lucas Cranach Penatua, Santo Christopher , C. 1509, potongan kayu chiaroscuro (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Potongan kayu Chiaroscuro

Seperti yang ditunjukkan oleh produksi potongan kayu berwarna tangan seperti Piet dan Madona Api , beberapa kolektor lebih menyukai intrik estetika dan emosional dari cetakan berwarna. Pada abad keenam belas, pembuat cetakan di Eropa utara dan Italia memanfaatkan minat itu dengan membuat cetakan balok kayu berwarna yang dikenal sebagai potongan kayu chiaroscuro karena mereka meniru tampilan gambar chiaroscuro. Dalam menggambar jenis ini, kertas berwarna berfungsi sebagai nada tengah di mana seorang seniman menambahkan pigmen putih untuk menghasilkan cahaya ( chiaro ) nada dan membuat lebih gelap ( skuro ) nilai dengan memasukkan tanda palka dengan pena atau area sapuan gelap dengan kuas. Konsep yang sama berlaku untuk potongan kayu chiaroscuro. Lucas Cranach's Santo Christopher , Misalnya, dibuat dengan dua balok kayu yang berbeda. Satu balok kayu, disebut sebagai blok nada, menciptakan nada tengah oranye. Balok kayu kedua, disebut blok garis, menghasilkan garis hitam, itulah desain dasar dan penetasan. Area kertas yang belum dicetak bertindak sebagai sorotan.

Contoh dari niello plakat, dengan desain linier menorehkan pada permukaan logam yang dilapisi dengan zat seperti pasta gelap. Diptych Renungan dengan Kelahiran dan Pemujaan , C. 1500, Paris, Perancis, perak, niello, paduan tembaga emas, 13,9 x 20,8 x 0,7 cm (Koleksi Serambi, Museum Seni Metropolitan)

Ukiran

Tidak lama setelah potongan kayu pertama dibuat, proses ukiran intaglio muncul di Jerman pada 1430-an dan digunakan di seluruh wilayah lain di Eropa utara dan selatan pada paruh kedua abad kelima belas (intaglio adalah kategori seni grafis yang mencakup ukiran, titik kering dan etsa). Ukiran tetap menjadi metode umum untuk seni grafis sampai akhir abad kedelapan belas sampai penemuan teknik planografi seperti litografi. Ukiran berakar pada tradisi bengkel tukang emas dan perak di mana niello plak—piring kecil dari emas atau perak—dibuat dengan menorehkan desain linier ke permukaan logam dan melapisi alur berukir itu dengan zat seperti pasta gelap untuk membuat representasi yang jelas.

Seniman menggores dan menggores pelat logam untuk menciptakan detail permukaan yang halus (video dari The Museum of Modern Art).

Burin yang digunakan dalam proses pengukiran (foto:Manfred Brückels, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Berbeda dengan proses relief potongan kayu, ukiran dihasilkan dengan memahat menjadi pelat tembaga menggunakan alat dengan ujung berbentuk permen yang disebut burin, yang meninggalkan alur berbentuk V. Setelah desain telah sepenuhnya menorehkan, seluruh permukaan pelat bertinta. Lanjut, pelat akan dibersihkan sehingga hanya tinta yang tertinggal di garis gores yang tersisa. Sekarang matriks siap dijalankan melalui mesin cetak dengan selembar kertas basah. Tekanan dari pers mendorong kertas ke dalam alur tersebut dan mengambil tinta, menghasilkan kesan cermin dari gambar yang terukir pada pelat tembaga.

Meskipun ini adalah salah satu ukiran paling awal Schongauer, itu sangat berpengaruh. Michelangelo bahkan menyalinnya. Martin Schongauer, Santo Antonius Disiksa oleh Setan , C. 1475, ukiran, 30,0 x 21,8 cm (Museum Seni Metropolitan)

Dibandingkan dengan kesulitan mengukir desain relief menjadi balok kayu, teknik pengukiran memungkinkan seniman yang terampil untuk menciptakan komposisi yang sangat detail dan bervariasi secara gaya tanpa takut menghasilkan garis yang terlalu sempit yang akan pecah di bawah tekanan mesin press. Salah satu pengukir terbesar di Eropa renaisans adalah Martin Schongauer. Miliknya St. Antonius Disiksa oleh Iblis memamerkan teknik ukirannya yang serbaguna.

Martin Schongauer, detail dari Santo Antonius Disiksa oleh Setan , C. 1475, ukiran, 30,0 x 21,8 cm (Museum Seni Metropolitan)

Untuk menghasilkan tekstur yang berbeda, Schongauer menggunakan berbagai tanda, seperti panjang, curling lines to render the soft fur on the demon brandishing a club short U-shaped lines to create the scales of the creature grabbing Anthony’s left arm. By incorporating passages of dense cross-hatching across Anthony’s body, Schongauer also gave his figure a three-dimensional presence on the flat paper surface.

Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer, who created ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor. Attributed to Kolman Helmschmid, etching attributed to Daniel Hopfer, Cuirass and Tassets (Torso and Hip Defense), with detail of Virgin and Child on the center of the breastplate, C. 1510–20, steel, leather, 105.4 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Etching

Another intaglio process that developed in Germany around 1500 and remained popular throughout the early modern period was etching. While engraving originated from the craft of gold- and silversmithing, etching was closely related to the armorer’s trade. Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer in Augsburg, a city in southern Germany. Hopfer discovered that through etching he was able to create ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor.

To etch an iron or copper printing plate, an acid-resistant substance (usually a varnish or wax) called a ground is applied to its surface. With a stylus or needle an artist draws a design into the ground, removing some of the coating each time a mark is made. After the design is complete, the plate is submerged into an acid bath and a chemical reaction takes place. The acid bites into the exposed metal, creating linear grooves. Once the plate is taken out of the bath and the ground is removed, the incised matrix is ready to be inked and printed in the same way as an engraving. Whereas engraving takes considerable manual labor because the printmaker has to carve into the metal plate, in the etching process, the acid does all of that work, and so it was considered an easier alternative to engraving. Artists who were adept at drawing, but not necessarily trained to engrave plates, found etching to be a suitable medium to make prints, since realizing a design in the ground with a needle was akin to drawing with a pen on paper.

Parmigianino, Entombment , 1529−1530, etching, 27.1 x 20.4 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Just like engraving, which had originated in Germany but quickly became popular among artists in other parts of Europe like Italy, etching also spread throughout the continent soon after its development. Parmigianino was one early sixteenth-century Italian painter and draftsman who tried his hand at etching. Miliknya Entombment shows off his expressive line work. It appears “sketch-like, ” resembling a pen-and-ink drawing rather than an engraving, which is usually characterized by regularized lines and marks of equidistant spacing and length.

First state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People , 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

Drypoint

Drypoint is perhaps the simplest method for creating an intaglio print. It developed at the same time as engraving in early fifteenth-century Germany, and like other related processes, drypoint attracted printmakers working across Europe. The technique involves using a stylus or needle to scratch into the surface of the copper matrix to throw up a burr. Just as the sides of a furrow or trench dug into the ground will hold drifts of snow, the raised edges of a drypoint line will retain ink. When making an engraving, the printmaker scrapes away the burr in order to achieve clean lines when the plate is printed. In a drypoint, however, the burr is left so that when the plate is printed, it produces a rich, velvety line. Unlike engraving, which can yield hundreds of decent impressions, the delicate drypoint burr wears quickly each time a plate is run through the press. Untuk alasan ini, drypoint was most often used to add finishing touches to compositions after the primary design had been engraved or etched. Belum, some printmakers like the seventeenth-century Dutch master, Rembrandt, preferred to work entirely in this technique.

Detail, first state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People, 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

Di dalam Christ Presented to the People , the contours of Pontius Pilate, Christ, and the surrounding soldiers reveal the dense, blurred character of the drypoint burr. Because drypoint created few quality impressions, Rembrandt often reworked his plates, making different states of the same image in order to produce more legible representations. The first state was printed early on in the plate’s lifetime before the burr began to wear. In the fourth state, the once-strong velvety lines have all but disappeared and changes to the architecture are visible. Most noticeably, the balustrade depicted near the upper right does not appear in the first state.

Fourth state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People , 1655, drypoint iv/viii, 35.8 x 45.4 cm (British Museum, London)

Mezzotint

Mezzotint rockers (photo:Toni Pecoraro)

The term mezzotint is a compound of the Italian words mezzo (“half”) and tinta (“tone”), and describes a type of intaglio print made through gradations of light and shade rather than line. To produce a mezzotint, an artist roughens the entire surface of a copper plate with a tool called a “rocker, ” a chisel-like implement with a semi-circular serrated edge. This tool is rocked back and forth across the plate until it has been completely worked, creating a surface full of burr that will hold ink. If you were to print an impression at this stage, it would appear as a field of rich black. To create a legible image, the printmaker must work from darkness to light with the aid of a scraper—a triangular-shaped blade fixed in a knife handle—and a burnisher—a blunt instrument with a hard, rounded end. By removing or smoothing out the burr, the artist weakens the plate’s capability to hold ink when the plate is wiped, and those areas will print a lighter tone.

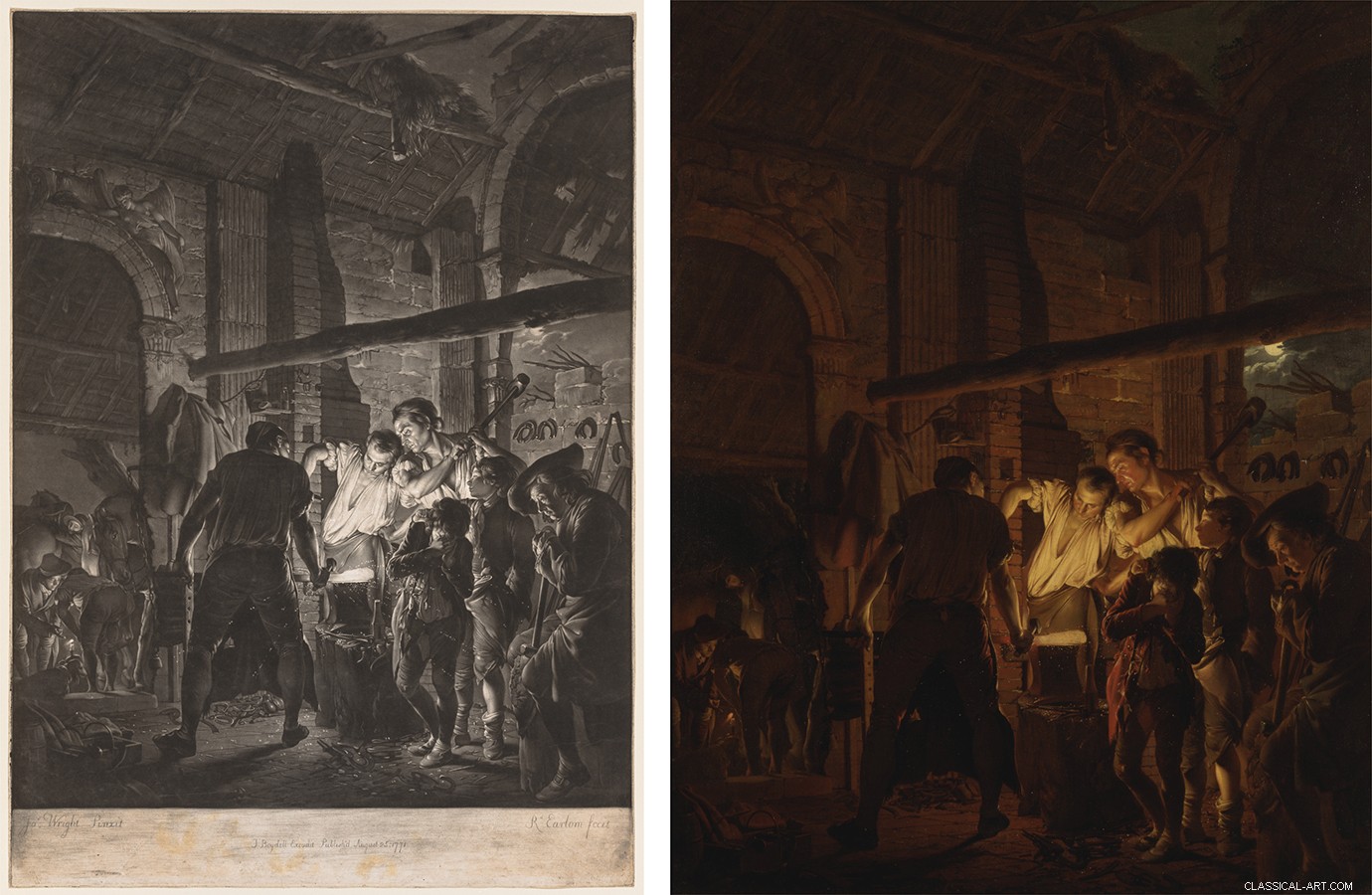

Left:Richard Earlom after Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop , 1771, mezzotint ii/ii (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland); right:Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop , 1771, oil on canvas, 128.3 x 104.1 cm (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven)

Although mezzotint originated in Amsterdam during the second quarter of the seventeenth century, it found particular appeal in eighteenth-century London, so much so that the medium was even nicknamed “the English manner.” When the Dutch-born sovereign William III became King of England in the late 1600s, numerous printmakers from the northern provinces of the Netherlands relocated to London in hopes of achieving royal patronage. During successive decades, native English artists learned from their Dutch contemporaries about how to make mezzotints and several technical manuals on the subject were also published locally. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, England had earned the reputation as a prolific center for mezzotint production. Richard Earlom was one English printmaker who had a successful career making mezzotint reproductions of oil paintings. The Blacksmith Shop from 1771 is based on Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting of the same subject. Wright’s pictures, which exhibit dramatic lighting effects, were ideally suited to be translated into mezzotint because the medium could capture the subtle tonal variations and lustrous appearance of his oil paintings.

Aquatint

Aquatint is a variant of the etching process that produces broad areas of tone that resemble the visual effects of watercolor. It involves the use of a powdered resin that is adhered to the plate through controlled heating. As the resin bonds to the plate, it creates a network of linear channels of exposed metal (think of how a cake of mud that is dried in the sun has a web of cracks). Once the plate is bitten by acid, the areas of exposed metal form deep grooves that are capable of holding ink.

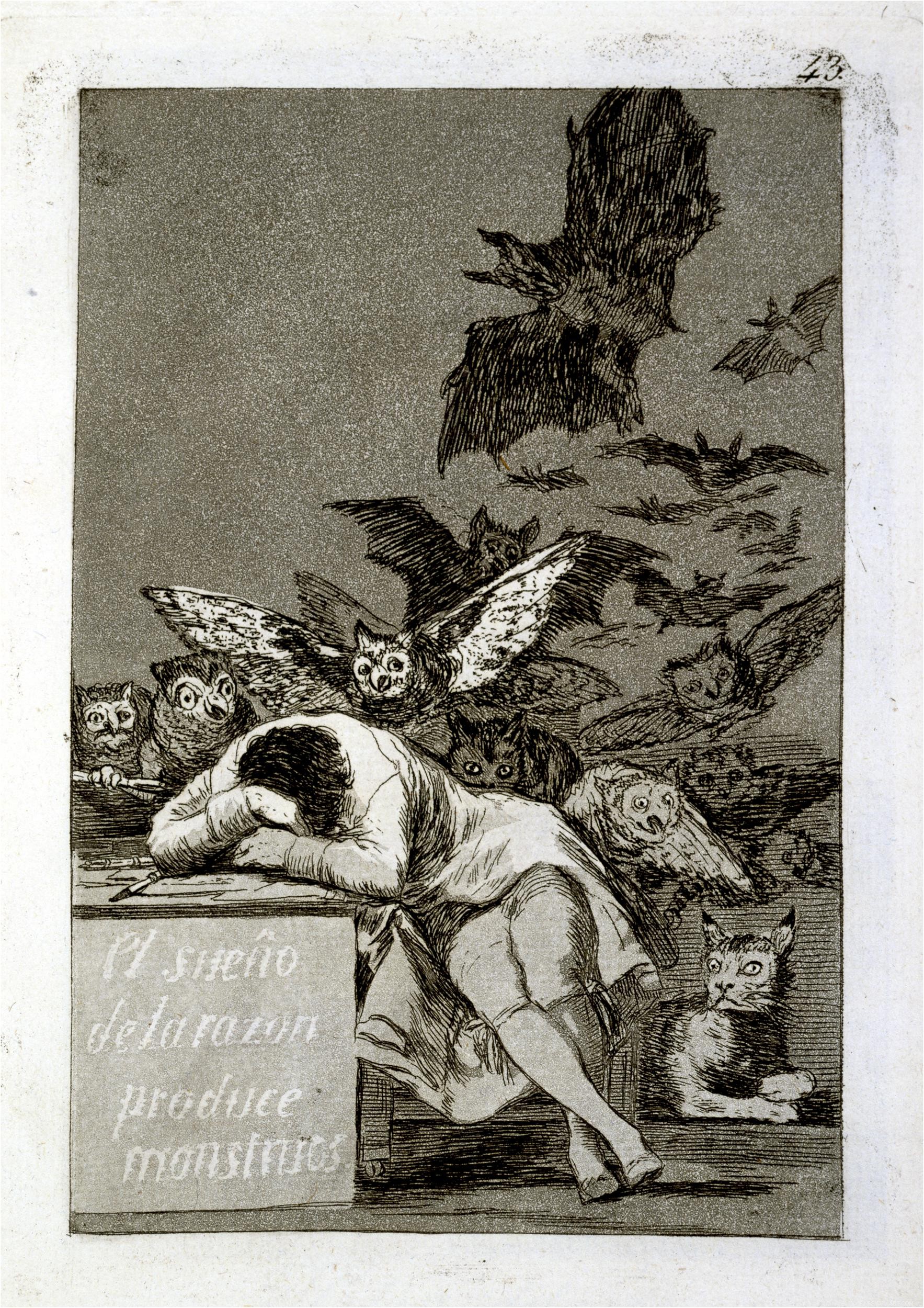

Francisco de Goya is famous for his artworks using aquatint. Goya, Los Caprichos:The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters , 1799, etching and aquatint, 21.2 x 15.0 cm (British Museum, London)

Aquatint was first introduced in the mid-seventeenth century in Amsterdam. Belum, unlike other printmaking techniques that found immediate attraction, it would take some time before aquatint became more widely used. By the late eighteenth century, several English etchers had become drawn to the more painterly qualities of aquatint, but the medium arguably achieved its greatest acclaim under the Spanish artist, Francisco de Goya. To make The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters , Goya first etched his sleeping artist, the bats, and haunting cat with quick lines. From there, he switched to aquatint to render the ominous shadow that envelops the entire composition and the white letters on the front of the artist’s desk.

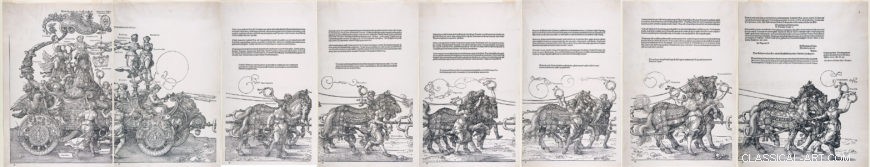

An example of a multi-sheet composition. Albrecht Dürer, Large Triumphal Carriage , C. 1518−1522, woodcut (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The business of printmaking

Printmaking in early modern Europe was a complex enterprise that involved a number of different agents. It was not always the case that the individual responsible for carving the woodblock or incising the metal plate was the designer of the composition. When Dürer was commissioned by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I to design a complex, multi-sheet composition of the Large Triumphal Carriage , he teamed up with a talented workshop of block carvers to help him execute that grand-scale project. In some workshops, the figure who undertook the physical process of printing the blocks and plates may have only done that job. Selain itu, there may have been a separate position dedicated to print publishing, that is selling and distributing the prints. Depending on the size of a workshop and the equipment available, some printmakers or publishers had to contract out some of those tasks. Sebagai contoh, if a publishing shop did not own a press, it had to collaborate with another local shop to produce its prints. Early printmaking revolved around a sophisticated network of artists and businessmen, and this legacy is still seen today. Many contemporary printmakers partner with a printing shop to create their work and/or a commercial gallery to exhibit and sell their art.

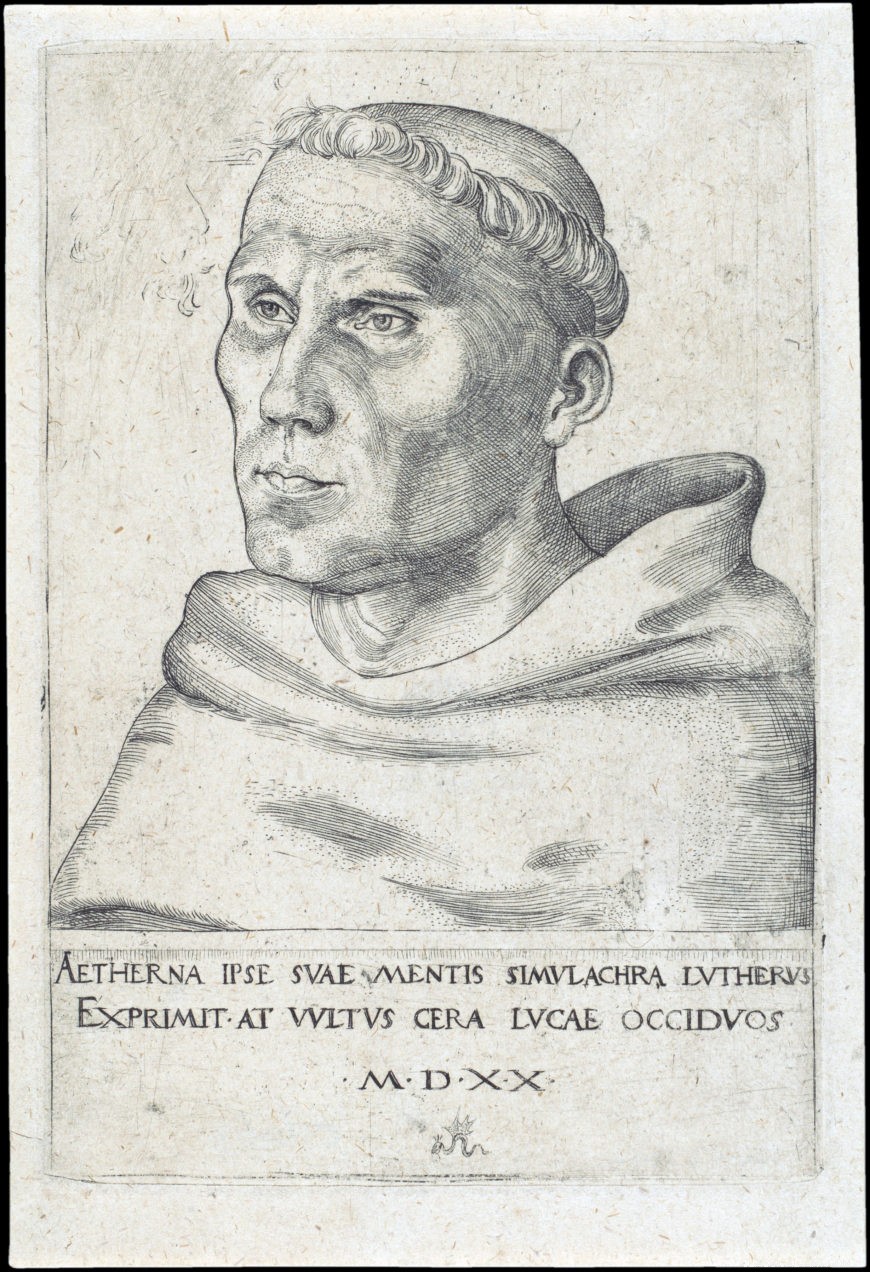

Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk and professor of theology in Wittenberg. He posted his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg—at least, this is how the tradition tells the story—that took issue with the way in which the Catholic Church thought about salvation, and it specifically took issue with the selling of indulgences. Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk , 1520, engraving, 15.8 x 10.7 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The advent of print not only transformed how images were made, but it created new possibilities for art collecting and mass communication. Scholars have long recognized how the mass distribution of printed pamphlets criticizing the Roman Church’s sale of indulgences and the pope’s supremacy along with printed portraits of Martin Luther, such as Cranach’s Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk , spurred on a religious revolution in northern Europe by promoting the agenda of Protestant Reformers.

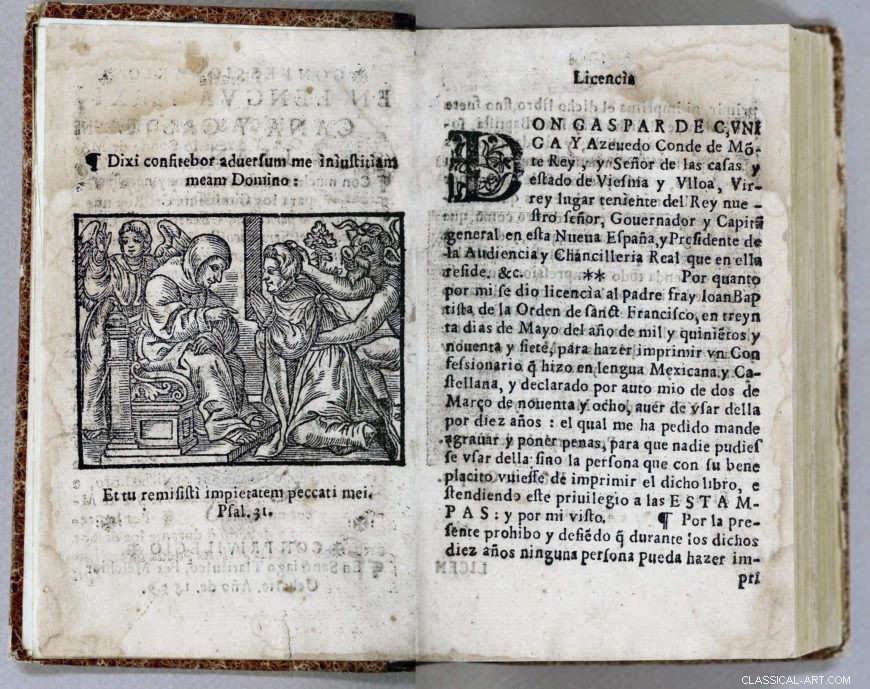

Books made in early colonial Mexico often stressed the importance of images in the process of converting Indigenous peoples. Juan Bautista, Confessionario en lengua mexicana y castellana [Preparation of the penitents in Nahuatl and Spanish] (Santiago Tlatelolco:Melchor Ocharte, 1599), 1v–2r (John Carter Brown Library)

The portability, reproducibility, and affordability of printed compositions contributed to the exchange of information and ideas between cultures of distant geographies. European missionaries who journeyed to the Americas beginning in the sixteenth century brought with them prints of biblical figures that were subsequently disseminated among Indigenous populations in an effort to convert those local communities to Christianity. This kind of imagery also introduced Indigenous artists to new iconographies, visual traditions, and technologies that greatly impacted the artistic production in the Americas. Faktanya, during the mid-sixteenth century, the first printing shop was established in modern-day Mexico City and a few decades later Peru transformed into another important center for printmaking in the southern hemisphere. What we consider to be “mass media” today, certainly has its origins in the early modern world of printmaking.